This article originally appeared in Desert

Magazine, May 1948--

The day is not far distant when motorists will

be able to roll along a smooth highway to a remote little

village on the gulf shore of Baja California and spend

their winter vacation days boating and fishing and bathing

in the hospitable atmosphere of Old Mexico---at San

Felipe. Here is a progress report on the new highway

to a locale many Southwesterners have long wanted to

visit.

by RANDALL HENDERSON

If those geologists who read the history of this old

earth in the rock formations and the alluvial deposits

have guessed correctly, the space now occupied by thc

Desert Magazine office in El Centro, California was

once many feet below the surface of thc Gulf of California.

This was a very wet spot.

But that was many years ago. The water is now gone,

and Desert's staff is warm and dry –52 feet below

sea level. Paradoxically, it was 0’l Man River---the

turbulent Colorado ---who did the engineering job necessary

to convert the great Imperial Basin, in which El Centro

is located, into one of the driest places on earth.

The muddy river with its delta on the eastern shore,

poured so much silt into the middle of the gulf a great

dam of sediment was formed creating an inland sea on

the upper part of this long slender arm of the Pacific.

After a few hundred years the salt water in this newly

formed sea evaporated, leaving the dry below-sea-level

plain to be discovered by Spaniards who came to the

New World in search of gold.

Then in the 1890's an American engineer, C. R. Rockwood,

came upon the scene and saw the possibilities of converting

this inland basin into farms, watered by the same river

that had created it. Today a half million acres in the

Imperial Irrigation district bear evidence of the soundness

of the idea. The 1947 production from this former gulf

bed was $96,000,000.

|

Before the lighthouse |

But the gulf---or what is left of it---still occupies

a very conspicuous place on the maps of North America's

west coast. True, it is growing smaller year by year

as the Colorado continues to pour its burden of silt

into the delta at the upper end. But it remains a sizable

body of water and one of the best deep sea fishing places

accessible to American fishermen.

When the boundary lines were set up between Mexico

and the United States, the shorelines of those gulf

fishing waters were allotted entirely to Mexico, and

Americans who would hook the 300 pound tutuava which

are so plentiful there have to travel many miles through

a foreign land, and one of the most arid desert regions

in the Southwest.

There are three roads from the Untied States to the

headwaters of the gulf. The best one is the oiled highway

that runs south from Ajo, Arizona to Punta Peñasco

on the Sonoran coast. Increasing numbers of sportsmen

are following this route each season.

A second road goes south from Yuma, Arizona through

the port of entry at San Luis to Puerto Isabel near

the mouth of the Colorado. This is a sandy road and

it is recommended only for the more adventurous traveler.

The third road starts at Calexico on the California

border and winds south across the delta to the fishing

village of San Felipe, 130 miles away on the Baja Califonia

side of the gulf. This story is concerned with that

road. It is a tortuous trail for an automobile. It is

used mainly for trucking the totuava (sea bass) and

shrimp caught in gulf waters to Mexicali, for reshipment

to southwestern markets. The trip involves 10 to 12

hours of punishing bumps and ruts, with no service facilities

along the way. Only the hardiest of the sports fishermen

ever attempt it.

But a new highway is being constructed from Mexicali

to San Felipe. It was for the purpose of giving Desert

Magazine readers a report on the new road that I made

the trip early in February. For, with a hardsurfaced

highway to San Felipe, this primitive little Mexican

fishing village 130 miles south of the border is destined

to become a popular mecca for both fishermen and tourists.

We had perfect equipment for such an expedition---three

jeeps. Arles Adams, my companion on many a desert exploring

trip, carried Larry Holland and Mike Thaanum as passengers.

Luther Fisher of the U. S. border patrol was accompanied

by two other patrolmen, Bill Sherrill and Harry Nyreen.

My passenger was Glenn Snow, manager of the Automobile

Club of Southern California office in El Centro.

It was still dark when we passed through the Calexico-Mexicali

port of entry at 5:20 a. m. Tourist permits had been

arranged in advance. There is no restriction on American

visitors crossing the line to Mexicali for a few hours.

But for an overnight trip beyond the municipal boundaries

a permit must be obtained either at the Mexican consulate

in Calexico, or at the Mexican immigration office at

the international gate. The cost of such a permit is

10.5 pesos, or $2.10.

Two routes are available for the first half of the

journey from Mexicali to San Felipe. The Laguna Salada

route is 18 miles longer than the direct road by way

of Cerro Prieto and El Mayor. But when the Laguna Salada

lake bed is dry, the longer route is less punishing

to man and vehicle.

We chose to make the southbound journey over the Laguna.

A glow of light was beginning to show on the eastern

horizon as we bumped along over the dirt road through

Mexican fields of alfalfa, cotton and grain stubble.

Fifteen miles out we left the cultivated lands of the

Baja California delta and climbed a low summit pass

through the Cocopah mountains.

Beyond the pass the road turned south across the level

sand bed of the lake, and for the next 68 miles we rolled

along at speed unlimited. This road over smooth baked

earth is a temptation to the driver. But occasionally

there are treacherous pockets of alkali and sand to

trap the unwary. Speed with caution is the rule across

the Laguna.

It is a delightful trip in the early morning as the

sun comes up over the Cucopahs on the east and brings

into sharp relief the rugged escarpments of the Sierra

Juarez on the west. Juarez range is slashed with deep

canyons where two species of wild palms grow in luxuriant

forests along little streams which head down toward

the floor of the desert but always disappear in the

sand before they reach their destination. The desert

escarpment of the Sierra Juarez is a virgin paradise

for the explorer, botanist, geologist, archeologist

and photographer. Its approaches are too rugged for

low-slung cars and picnic parties. One needs a jeep

or a hardy pair of hiking legs to get far into the canyons

of that little known range.

As we neared the lower end of the Laguna we saw a

low embankment across the pass ahead of us. When we

arrived there a few minutes later we discovered this

was the grade of the new San Felipe highway.

The new road, costing millions of pesos, is under

construction for 70 miles south of Mexicali. Part of

the way it is a graded embankment across the overflow

lands. At one place it leaves the floor of the delta

plain and cuts through a pass in the Pinta mountain

range.

We followed the incompleted roadbed a few miles, but

below El Mayor a half dozen construction crews are working

on different sectors and continuous passage on the new

roadbed is still impracticable.

Leaving the new grade we headed south across the great

salt flat which lies around the head of the gulf on

the California side. This flat is composed of Colorado

river silt highly impregnated with salt and alkali.

Imagine a great salty plain so arid not a bug or a blade

of grass lives there, and so vast the curvature of the

earth prevents your seeing across it---and you have

a good picture of the terrain we are covering. It is

as level as a floor, and when wet becomes a bottomless

quagmire.

Little rain has fallen on that area for three or four

years, and the road across the flat is in the best condition

I have known in 15 years. However, there are high centers

in places and it is never possible to roll across this

plain at high speed as one does on the bed of Laguna

Salada.

Once, many years ago, Malcolm Huey and I tried to

cross this salt desert too soon after a rain. We plowed

along in our pickup for miles and finally bogged

down near the middle of it. Then the motor quit and

we were not mechanical enough to fix it. We ran out

of water, but had a bag of grapefruit in the car---and

that is mostly what we lived on for two days until a

fish truck carne along and hauled us into port.

A hundred miles below Mexicali we left the salt plain

and rolled along over the coastal bench which borders

the gulf at this point. Here we caught our first glimpse

of senita (old man cactus) and elephant trees

which grow thickly in the Baja California desert. Desert

vegetation is prolific here, and most of the trees and

shrubs are the old friends of the Lower Sonoran zone

with which we are familiar in the deserts of Southern

California and Arizona---ironwood, palo verde, ocotillo

and creosote. We saw salmon mallow, chuparosa, locoweed

and lupine in blossom. Mexicans call this coastal plain

Desierto de los Chinos--- Desert of the Chinese.

A tragic story lies at the back of that place name.

According to well-confirmed reports, the captain of

a Mexican power-boat many years ago picked up a load

of Chinese at Guaymas on the Mexican west coast. They

wanted to go to Mexicali where many of their countrymen

were, and still are, in business, and paid him well

for the passage. At San Felipe bay the captain put them

ashore and motioned inland. "Mexicali is just over

the hill," he told them. It was rnidsummer and

the Chinese started inland practically without water

or food. Days later two of them stumbled into a cattle

camp many miles to the north. The rest perished from

heat and thirst. Occasionally one comes across an unmarked

grave in that region.

Driving through the dense growth of ironwood, palo

verde and elephant trees one catches an occasional glimpse

of the blue waters of the gulf three or four miles away

to the east. On the west the San Pedro Martir range

rises to an elevation of more than 10,000 feet, capped

by Picacho del Diablo, highest peak on the Lower California

peninsula. Three times I tried to climb that peak from

the desert side, and finally made it to the top with

Norman Clyde in 1937. The story of that rugged adventure

in unmapped mountain terrain will be told in a future

issue of Desert.

Ten miles before reaching San Felipe a side road takes

off down an arroyo to the golf shore at Clam Beach.

The sandy waterline here is strewn with sea shells,

tons of them extending along the shoreline for miles.

I know little about the classification of shells, but

I am sure this place is a paradise for collectors. We

gathered some of the prettiest conches for souvenirs,

and then drove the last leg of our journey into San

Felipe.

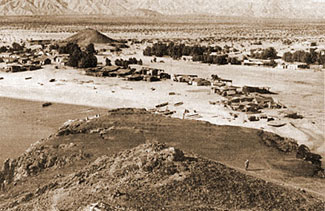

|

Before the real estate

rush. |

It was 3:30 when we arrived at the little shack on

the edge of the settlement which serves as a customs

house, and passed inspection. The Mexican officials

were friendly, but were sorry to inform us that the

water in the gulf was too rough for fishing just now.

They could not understand why anyone would come to San

Felipe if not for fishing. We explained we had driven

down to learn about progress on the new road, and about

the million dollar resort which, according to American

newspaper reports, has been under construction for some

time.

We visited the hotel site, on a bluff overlooking the

bay of San Felipe. It is an imposing site, with an airplane

runway along the beach below. But the only construction

work in progress is a substantial adobe dwelling which

we were told is to be the home of the engineer who is

to erect the hostelry. San Felipe residents --there

are about 1000 of them---were divided in their predictions

as to the hotel. Some were confident it would be built.

Others were skeptical. My own conclusion was that it

hardly would be a feasible project until the new road

to San Felipe is completed--probably in another

year.

Located in a cove on the shore of the bay, the sprawling

village hasn't much to boast about in the way of architecture.

But it is a lovely site, and despite the primitive conditions

of their existence I am sure there are no happier people

on earth than these Mexican fishermen and their families.

Fishing is the sole industry. Trucks from Mexicali

haul ice on the southbound trip, and bring back fish

packed in ice. The fishing season lasts through the

winter months, and when it is over many of the families

return in their boats across the gulf to their permanent

homes in Guaymas and other Mexican west coast ports.

Jose Verdusco, owner of a truck, was having a day

off because there were no fish to haul, and he volunteered

to serve as our guide. We paid a courtesy call at the

home of Francisco Benjarebo de Chica, former police

chief in Mexicali who is now the law in San Felipe.

Then we went to the two town wells, dug in the sand

along the bluff back of the village.

Nature has been kind to the housewives in this remote

hamlet. In one well the water comes to the surface warm.

This is the laundry well, where the women do their washing.

A half mile away another well has cool water for drinking.

All day long the men of the village may be seen trudging

to and from the well with two 5-gallon gas cans strung

on a palanca across their shoulders. To them it is no

hardship that every drop of domestic water must be carried

from the well, perhaps a mile away, along a sandy trail.

Perhaps it is because the chores of everyday living

require constant and arduous labor that San Felipe has

seldom needed the services of a doctor.

San Felipe is a town practically without glass. And

after you have driven over the only road by which glass

might be transported, you will understand this. The

buildings are mostly adobe, with variations of wood

and sheet iron, hauled from Mexicali or brought across

from the Sonora side in boats.

Parties of sportsmen who wish to charter a boat for

fishing are charged from $40 to $50 a day for power

boat and crew plus expert information as to the where

and how of totuava fishing. There is no fixed

fee for individuals who go out as passengers on the

regular daily fishing trip. They settle for a generous

tip to the skipper.

Jose Verdusco took us to the top of a rocky point

which flanks the village on one side, to a little lighthouse

which serves as a beacon for fishermen caught out on

the gulf after dark. The acetylene lamp was located

in a tiny cupola over a shrine where a wax figure of

Guadalupe, patron saint of the San Felipe pescadores,

reposes in a setting of candles and other altar symbols

of the Catholic faith.

Forty-one fishing boats were anchored offshore. There

is no wharf. They were waiting for better fishing weather.

The fishermen loafed on the sand, or repaired their

nets. Wood-cutters with burros make excursions into

the surrounding hills and bring in firewood.

San Felipe lives at peace with itself and the world---untroubled

by lack of such things as running water, window panes,

inside toilets, street lights and motor cars. In American

communities we regard such things as essential---and

often overlook the price in spiritual values we have

to pay for them.

We camped that night a few miles out of San Felipe

near a little forest of elephant trees. We used some

of the dead branches for firewood. This was my first

experience cooking a camp dinner on this species of

wood. It made a brisk warm fire with a pleasing aroma.

On the return trip we followed the same route through

the desert of the ghosts of hapless Chinese and thence

across the great salt wasteland. It was midday and mirages

simmered on the horizon in all directions. Often we

were completely surrounded by "water." Spurs

of the Pinta mountains projecting out into the flat

appeared to be floating islands. A tiny bush appeared

as big as a tree. A car coming from the opposite direction

went through strange contortions. At one moment it resembled

a fat squatty house and the next moment it was as skinny

as a telephone pole.

Below El Mayor we climbed to the newly constructed

roadbed. It has been topped with rock, and although

not finished, it already is a much better road than

the old trail the fish trucks have followed along the

Cocopahs for many years. El Mayor is a little settlement

of three or four crude buildings on the banks of the

old Hardy channel. Since the completion of Hover dam,

the delta is not subject to the annual flood overflow

which spread over the entire delta in former years.

Mexican farmers are bringing more and more of these

fertile delta acres under cultivation, and farms line

one side of the road far below El Mayor.

We wanted to follow the new road all the way back

to Mexicali, but when we reached a point opposite the

volcanic crater of Cerro Prieto, a bridge was out and

we had to detour to the old road to Palaco and thence

to the border gate.

Our log showed 136 miles to San Felipe by the El Mayor

route, and 154 miles by way of Laguna Salada. One may

reach the fishing village by either of these routes,

but it is a punishing trip for a good car. At a later

date when the new highway is completed this will be

an inviting excursion for desert motorists seeking new

landscapes.

Perhaps San Felipe will then have hotels and window

panes and water hydrants and service stations. These

civilized inventions will remove much of the physical

discomfort and mental hazard of a trip to San Felipe.

But I am not sure they will either add to or detract

from the charm of this remote little fishing village

on the shores of the ancient Sea of Cortez.